Scaffolding Strategies for K-12 Teachers: What You Need to Know

A teacher’s job is not simply presenting information for students to absorb, and teaching does not mean learning. An educator is responsible for ensuring that students develop an understanding of core concepts and themes as well as develop skills to transfer knowledge to new settings inside and outside of the classroom. And while teachers can present information in various ways to engage learners, modeling challenging activities or introducing new concepts to students is only the first step. To help students understand a new concept or grasp how to complete a task on their own, many educators rely on scaffolding to gradually shift the student towards independent learning

What is Instructional Scaffolding?

Fundamentally, scaffolding is the practice of breaking up learning into smaller chunks to expose students to more complex material in stages. Distinct from differentiation which utilizes different methods to present material to students based on their needs, scaffolding uses strategies that present content or experiences to students in increasingly complex portions to allow them time to make sense of and more fully absorb new knowledge. But scaffolding at its heart, regardless of the method used, is the gradual release of the educator from ownership within the learning process, allowing the student agency for their learning journey.

The Basics of Scaffolding

This instructional method is founded on three basic stages of learning:

- What the learner does not know or cannot do by themselves

- What a student can do or understand with support or guidance

- What a student can do or understand independently

Scaffolding aims to move students from being able to complete a task or understand a concept with assistance to being able to accomplish it or understand a concept on their own.

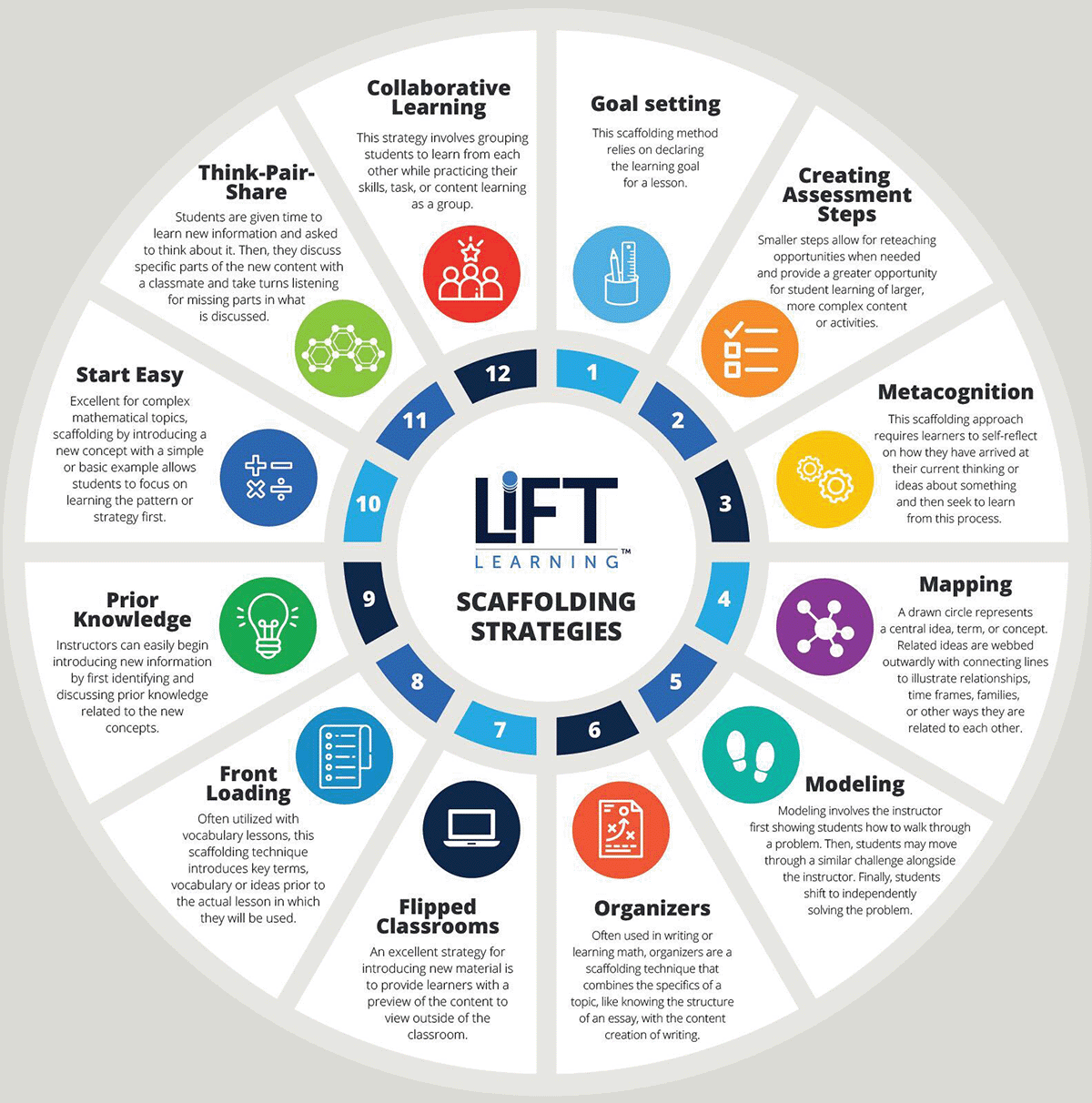

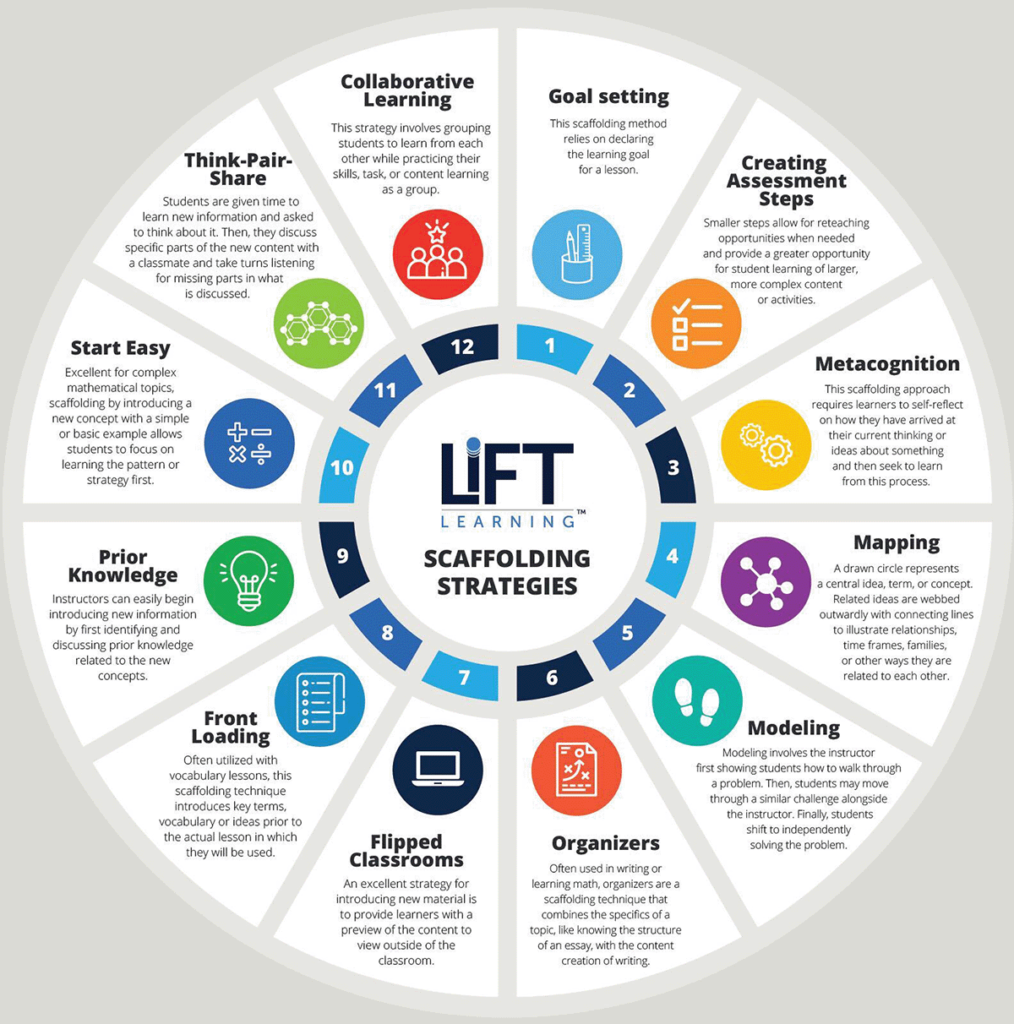

12 Scaffolding Strategies

Depending on the student’s age, prior knowledge, and subject area, different strategies for scaffolding may be used. Below are 12 ideas for activities and assessments to use when scaffolding your next lesson.

- Goal Setting – Everyone likes to know ahead of time where they are headed when they start on a journey, and students are no different. This scaffolding method relies on declaring the learning goal for a lesson. Students will know what the result should look like or what they should know by the end. They will be able to absorb the steps or stages to achieve what success looks like more readily since they can begin to anticipate the knowledge goal or skill and recognize when they have been successful with the stated goal. This same scaffolding practice can be flipped by asking learners to set their own goals and then discuss how they can achieve that learning goal by applying previous knowledge or abilities.

- Creating Assessment Steps – Instead of only utilizing summative assessments, including formative assessments along the way as one of the scaffolding strategies in the classroom can help inform both the instructor and the learner. Summative assessments can also be submitted in small steps or chunks to provide feedback to the learner on larger projects, papers, or assignments. These smaller steps allow for reteaching opportunities when needed and provide a greater opportunity for student learning of larger, more complex content or activities.

- Metacognition -Perfect for the older learner but effective with younger students as well, metacognition is the art of “thinking about thinking.” This scaffolding approach requires learners to self-reflect on how they have arrived at their current thinking or ideas about something and then seek to learn from this process. Students may find connections to other things they have previously learned or heard about but do not yet have knowledge about, or they may discover how their thinking about a topic can be improved or enhanced. Instructors can model metacognition for students to understand how to think about their own thinking using a visual aid, mapping, or simply explaining what their own thinking pathways look like to help them begin for themselves.

- Mapping – Creating a physical representation of relationships is one of the scaffolding strategies that help students see physical relationships between known and potentially unknown concepts. Start with drawing a circle to represent a central idea, term, or concept. Related ideas are webbed outwardly with connecting lines to illustrate relationships, time frames, families, or other ways they are related to each other.

- Modeling – Thought of as one of the original scaffolding strategies, modeling involves the instructor first showing students how to walk through a problem, exercise or new content knowledge one or more times, depending on the complexity of the knowledge. Then, students may move through a similar challenge alongside the instructor to see the process again as they begin to join in the process. Finally, students shift to independently solving the problem when the modeling has produced confidence in the students to be able to attempt it alone.

- Organizers – Often used in writing or learning math, organizers are a scaffolding technique that combines the specifics of a topic, like knowing the structure of an essay, with the content creation of writing. Students may be given an increasingly less detailed organizer that guides them along the process of creating an essay with the ultimate goal of the student being able to create their own organizer from scratch in their pre-writing process that correctly formulates the structure of a well-planned, complete essay.

- Flipped Classrooms – An excellent strategy for introducing new material is to provide learners with a preview of the content to view outside of the classroom. Commonly referred to as “flipped,” this strategy involves video, reading, or other media presentations of new content for students to explore on their own prior to coming to class. This pre-exposure to the new information provides learners with a first look so they can begin to connect their own prior knowledge to the new content without the typical time constraints required in a class period.

- Front Loading – Often utilized with vocabulary lessons, this scaffolding technique introduces key terms, vocabulary, or ideas prior to the actual lesson in which they will be used. Similar to the scaffolding methods of a flipped classroom, front-loading provides students time to hear, see and practice new terms or ideas prior to needing to have that knowledge accessible during a content-based lesson. This early exposure to keywords or content allows for potentially greater and deeper absorption of new content in the long run since learners first hear and see the important terms and then learn how and when to use them once they have a basis for understanding them.

- Prior Knowledge – Instructors can easily begin introducing new information by first identifying and discussing prior knowledge related to the new concepts. This provides a basis for understanding the new information as well as reminds students what they already know and how the new content is connected in a larger sense.

- Start Easy – Excellent for complex mathematical topics, scaffolding by introducing a new concept with a simple or basic example allows students to focus on learning the pattern or strategy first. Once proficient, students can move on to more complex or complicated applications of the pattern or strategy.

- Think-Pair-Share – Similar to collaborative learning, this strategy is sometimes called “turn and talk.” Students are given time to learn new information and then asked to think about it. Then, they will discuss specific parts of the new content with a classmate and take turns listening for missing parts in what is discussed. The process is repeated or modified in ways that solidify learning new content or illuminate student questions.

- Collaborative Learning -Most strategies are led by the instructor but students inevitably come to the classroom with prior knowledge as well as strengths and weaknesses. This strategy involves grouping students to learn from each other while practicing their skills, task, or content learning as a group. Collaboration with peers allows students time to grasp new concepts in a relaxed setting while having the opportunity to encourage or teach others what they know or can do.

As a New Hampshire educator at the forefront of the competency-based movement, Joey taught Cultural Geography in grades 9-12 at Pinkerton Academy. He was awarded New Hampshire’s Teacher of the Year in 2014 before taking a leadership role as Director of Education at Education First. At EF, he was responsible for improving the learning experience of participants in travel programs through accreditation, strategic partnerships, and product development.